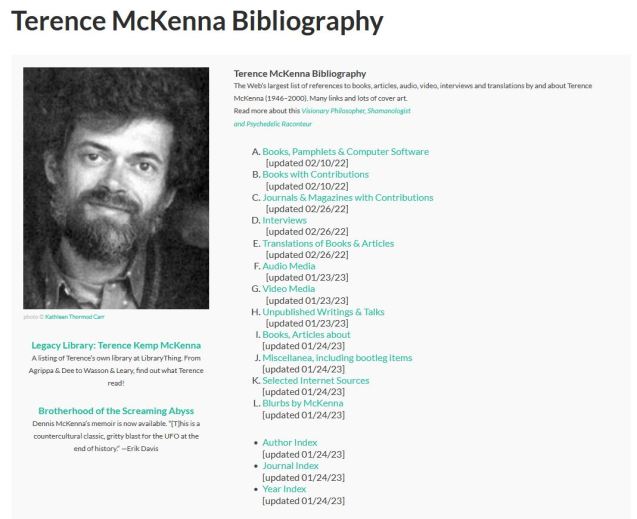

As I work on updating the Terence McKenna Bibliography, I am also acquiring new material for the archive as a reflection of how Terence McKenna’s name and ideas have been (and continue to be) represented. This is a digest of some of the new material coming into the collection at the moment.

Drunk the Night Before: An Anatomy of Intoxication by Marty Roth (2005), University of Minnesota Press

Just because the story of drugs as spiritual degeneration is insistently repeated doesn’t make it true. True and false states of exaltation may not be as different as cultural arbiters claim, since the institutions and images that compose our religious history have been airbrushed by denial, or, shifting to Terence McKenna’s similitude: “There are skeletons in the closet of human origins and of the origin of religion. I would wager that those skeletons are all psychedelic plants.” (p. 86)

Terence McKenna believes that the “intake of psilocybin by primates living in the African grasslands prior to the last Ice Age may have led to the origins of human language itself.” (p. 156)

The alignment of Wordsworth and Coleridge with water and wine also rhymes with the alternate goals they set themselves in modern poetry: poems of ordinary life as opposed to supernatural subjects that give “the interest of novelty by the modifying colors of imagination” (Coleridge 168). Terence McKenna tries to refine this model further: “Opium was a major driving force on the Romantic imagination–Coleridge, De Quincey, Laurence Sterne, and a number of other writers were creating a world of darkened ruins, abandoned priories, black water sucking at desolate shores–clearly a gloss on the opium state. Then around 1820, Byron, Shelley, and others began experimenting with hashish as well…. [but it] never made inroads into the English literary imagination the way that opium had.”

Culture on the Brink: Ideologies of Technology edited by Gretchen Bender + Timothy Druckrey (1994), Bay Press

In Margaret Morse’s chapter, “What Do Cyborgs Eat? Oral Logic in an Information Society,” Terence McKenna is mentioned several times:

There are certain recurring features in the very limited literature on smart drinks and drugs in how-to books, manifestos, and ads in Mondo 2000: smart nonfood tastes bad–medicinal, in fact; smart drugs are better than nature, once one achieves the right “fit” between brain and chemicals; and they improve performance in mental tasks. To at least one countercultural theorist, Terence McKenna, smart drugs, insofar as they are psychotropic, are in fact Food of the Gods, at once archaic and posthistorical tools toward the next phase of human evolution toward colonizing the stars. (p. 182)

Smart drug “fit” is not based on existing “natural” quantities–neurochemicals are too costly for the body to make in beneficial amounts. However, according to Terence McKenna, nature has offered psychoactive drugs, which are not merely smart but, he claims, have spurred human mental evolution, in abundance. In Food of the Gods, McKenna explains, “My contention is that mutation-causing, psychoactive chemical compounds in the early human diet directly influenced the rapid reorganization of the brain’s information-processing capacities. Alkaloids in plants, specifically the hallucinogenic compounds such as psilocybin, dimethyltrypta-mine [sic] (DMT), and harmaline, could be the chemical factors in the proto- human [sic] diet that catalyzed the emergence of human self-reflection.” McKenna views the fifteen thousand years of cultural history between the archaic period and the present as “Paradise Lost,” a dark age of ego-imbalance to be abandoned, along with “the monkey body and tribal group,” in favor of “star flight, virtual-reality technologies, and a revivified shamanism.” Again, the archaic and the electronic are united.

Out of Character: Rants, Raves, and Monologues from Today’s Top Performance Artists edited by Mark Russell (1997), Bantam Books

In the profile for the artist, performer, puppeteer, and creator of magical objects, James Godwin, Terence McKenna’s books The Archaic Revival and True Hallucinations appear in Godwin’s “Reading List.”

In the profile for the artist, performer, puppeteer, and creator of magical objects, James Godwin, Terence McKenna’s books The Archaic Revival and True Hallucinations appear in Godwin’s “Reading List.”

Inward Journey: Art as Therapy by Margaret Frings Keyes (1983), Open Court

This represents a relatively early awareness of and reference to the McKennas based on an encounter with the 1st edition (1975) of The Invisible Landscape. It gets some details wrong, such as Mexico v. Colombia.

…if she [a patient] learnt the hard way within the active imagination to overcome the obstacle, she would have also learnt something for outer life. Even if a patient was stuck in active imagination over weeks Jung did not give a helpful suggestion but insisted that he or she should continue to struggle with the problem himself and alone.

In controlled drug-taking this forth step is again missed. The controlling person carries the responsibility instead of the producer of the phantasy. I came across an interesting book by two brothers Terence and Denis [sic] McKenna: The Invisible Landscape. These two courageous young men went to Mexico [sic] and experimented on themselves with a hallucinogenc plant. They experienced according to their own report schizophrenic states of mind, which led to a great widening of consciousness. Unfortunately they could not keep track of the experiences except that they went to other planets and were often helped by an invisible guide who was sometimes a huge insect. The second part of the book contains the speculations which they derived from their visions. They are not different from any other wildly intuitive modern speculations about mind, matter, synchronicity, etc. In other words they do not actually convey anything really new or which the two well-read authors could not have thought out consciously. But what is decisive is the fact that the book ends with the idea that all life on earth will be definitively destroyed in an approaching cataclysm and that we must either find means to escape to another planet or turn inward and escape into the realm of the cosmic mind. Let me kcompare this with a dream which an American student allowed me to use and which is concerned with the same theme…

Soul Seeds: Revelations & Drawings by Carolyn Mary Kleefeld; Foreword by Laura Huxley (2008), Cross-Cultural Communications

And to my mentors and beloved comrades who inspire from beyond the concept of death, Dr. Carl Faber, Edmund Kara, Barry Taper, Freda Taper, Dr. Timothy Leary, Dr. Oscar Janiger, Terence McKenna, Nina Graboi, Dr. John Lilly, William Melamed, and the unmentioned others. (Acknowledgements)

Carolyn is interviewed along with Allen Ginsberg, Terence McKenna, Timothy Leary, Laura Huxley and others in Mavericks of the Mind: Conversations for the New Millennium by David Jay Brown & Rebecca Novick. THE CROSSING PRESS, FREEDOM, CA 1993 (p. 91)

Terence McKenna also wrote a blurb that appears on the back of Kleefeld’s book The Alchemy of Possibility: Reinventing Your Personal Mythology (1998):

“A wonderful mature amalgam of esthetic intention. Congratulations!”

— Terence McKenna, author of The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens and the I Ching

How to Be Idle by Tom Hodgkinson (2005), HarperCollins

An interview with Terence McKenna by Hodgkinson appeared in the inaugural first issue (August, 1993) of his journal The Idler. The Terence McKenna Archives does not currently own a copy of this 1993 publication. If you have a copy that you would like to scan, send, or sell, please get in touch.

An interview with Terence McKenna by Hodgkinson appeared in the inaugural first issue (August, 1993) of his journal The Idler. The Terence McKenna Archives does not currently own a copy of this 1993 publication. If you have a copy that you would like to scan, send, or sell, please get in touch.

In this 2005 book, Hodgkinson sprinkles references to McKenna throughout:

It is precisely to prevent us from thinking too much that society pressurizes us all to get out of bed. In 1993, I went to interview the late radical philosopher and drugs researcher Terence McKenna. I asked him why society doesn’t allow us to be more idle. He replied:

I think the reason we don’t organise society in that way can be summed up in the aphorism, “idle hands are the devil’s tool.” In other words institutions fear idle populations because an Idler is a thinker and thinkers are not a welcome addition to most social situations. Thinkers become malcontents, that’s almost a substitute word for idle, “malcontent.” Essentially, we are all kept very busy … under no circumstances are you to quietly inspect the contents of your own mind. Freud called introspection “morbid”–unhealthy, introverted, antisocial, possibly neurotic, potentially pathological. (pp. 33-4)

“UFOs, the theory goes, are simply folk like us who evolved on another planet and have a more advanced technology,” the late Terence McKenna once remarked. “It doesn’t straing credulity in the way that hypothesizing that we’re in contact with an afterworld or a parallel continuum challenges our notion of reality.” (p. 187)

Robert Louis Stevenson used his dreams to create plots and characters for his stories. Little creatures which he called Brownies revealed stories to him. He said, “My Brownies do one half of my work while I am asleep.” Stevenson’s Brownies sound a bit like the “chattering elves of hyperspace” cited by Terence McKenna as one of the key elements of the experience of taking the drug DMT: mischievous, scampish, truth-giving sprites and fairies. (pp. 264-5)

Exploring the Labyrinth: Making Sense of the New Spirituality by Nevill Drury (1999), Continuum

Published by the same company that published the first edition (1975) of The Invisible Landscape (Continuum was then a subsidiary of Seabury Press), this is not Drury first time mentioning McKenna in his work. This will make a fifth entry for Drury in the Bibliography.

Finally, in an overview that links native shamanism with the New Spirituality, mention must be made of the unique and potentially revolutionary vision of Terence McKenna. One of the most controversial and illuminating figures to have emerged from the counter-culture, and arguably the most obvious spiritual successor to Timothy Leary, McKenna is renowned for his gift of eloquent dialogue. In any of his lectures or media appearances he will, more likely than not, amaze his audience with eclectic references to shamanism, visionary literature, psychedelics, UFOs, alchemy and the mystical traditions. But shamanism itself is central to his contribution to contemporary transpersonal perspectives.

McKenna believes that the shamanic model of the universe is not only the most archaic but also the most accurate we have, and that we should heed shamanic traditions and practices in our efforts to map the psyche. He also believes that since research into psychedelics has been banned by governmental authorities–a consequence both of recklessness of the counter-culture as well as the power politics of the establishment–valuable insights into the potentials of consciousness are in danger of being overlooked at a crucial time in our history.

From pages 143-146, Drury goes on to devote the entirety of his attention to McKenna, concluding with:

For him, shamanism is nothing less than the best map we have of consciousness in the modern era, a map which allows us awe-inspiring access to the very core of our being and to the soul of the planet itself. From his perspective, nothing could be more profound or significant than that.

Drury also includes a brief, fairly standard, bio of Terence on page 201: “McKenna, Terence (1946 – );”

The penultimate entry for today’s acquisitions update (I’ll be back with more soon) is the satirical:

Generation Ecch! The Backlash Starts Here by Jason Cohen and Michael Krugman, Comix by Evan Dorkin (1994), Fireside

Cyberpunk hypothesizes that the new technology is a gateway to God. All these years man has been mystified by the divine phenomenon of speaking in tongues, and it turns out it was just PASCAL. Add some drugs to the mix, and you’ve got an idyll of technospiritualism.

If this scene has a guru, it’s the man Timothy Leary himself has called “the Timothy Leary of the nineties,” writer and self-acclaimed prophet genius Terence McKenna. At fortysomething, McKenna is neither neo or retro in his preaching–rather, he’s an actual hippy, a guy who still hangs out in Berkeley and Big Sur exploring the transcendental self-actualizing utopian possibilities of psychedelic drugs. Unsurprisingly, McKenna’s solution to most global and individual problems is what he calls the “heroic dose” of psilocybin, better known as ‘shrooms dude.

McKenna has said that the magic morels speak to him, but the revelations he experienced while drooling in dark corners under the influence are not exactly original. For one thing, they told him to take a .45 and go kill Stacy Moskowitz. Son of ‘Shroom! But seriously … the talking toadstools actually delivered the shocking information that the ecosystem is in trouble! Or perhaps Al Gore was plugging his book Larry King Live while Terence was tripping.

The anthropomorphic fungi have also told him that the way to solve the world’s environmental crisis is to take more ‘shrooms. Cool! It beats composting.

In the wee small hours of the morning, the disciples of cybercrap and McKennan catechism can be found at abandoned warehouses and isolated meadows, where, garbed in Day-Glo rain gear, enormous bell-bottoms and Cat in the Hat chapeaus, they harmoncially converge at futuristic be-ins known as raves. Bearing fluorescent pacifiers ’round their necks and backpacks crammed with Yodels, Silly String and VapoRub, they get juiced on nootropics and find sustenance in the nourishing sugar and caffeine of Jolt cola. Other nutritional requirements are fulfilled with large colorful hanfuls of crunchy yummy Flintstones vitamins. Unapologetically escapist, fatuously optimistic and barely sybaritic, these festivities meld digital technology and New Age posturing with elements of previously viewed youth culture: disco’s party! party! mentality, the frenzied spasmodics of punk, psychedelic pspirituality and that old favorite, the Dionysian bacchanal. (pp. 166-8)

And, finally for today’s post (see you next time):

Big American Trip by Christian Peet (2001), Shearsman Books

This collection of fictional postcards, as you no doubt anticipate, includes a mention of Terence McKenna:

Says the Alien Terence McKenna:

“The starships of the future, in other words the vehicles of the future, which will explore the high frontier of the unknown, will be syntactical. The engineers of the future will be poets.”

[Addressed to:] NASA/DOD, Ames Research Center, Mountain View, CA 94035

the Angeles National Forest along with Bruce Damer (whose continued work on the problem of the origins of life on Earth has received renewed attention in

the Angeles National Forest along with Bruce Damer (whose continued work on the problem of the origins of life on Earth has received renewed attention in